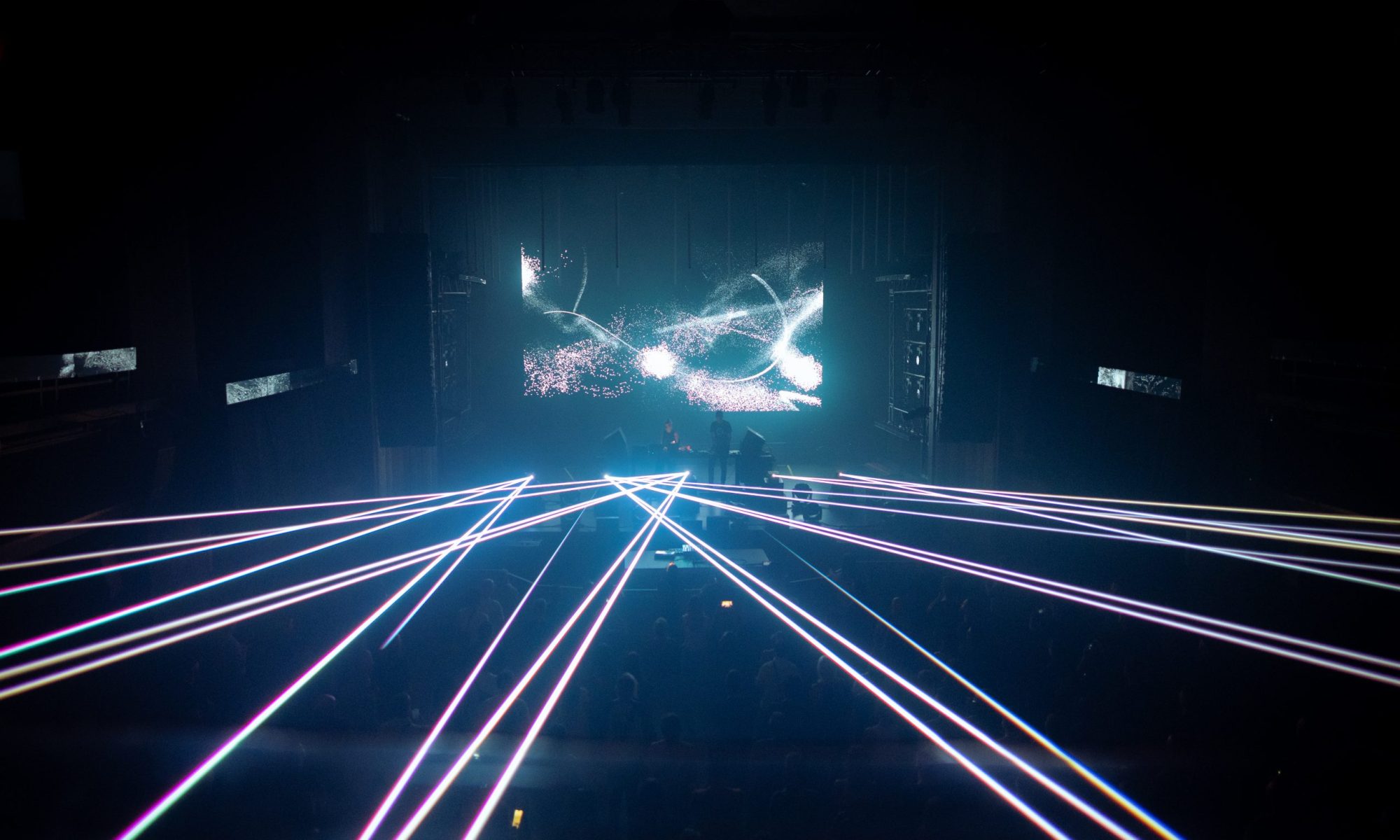

photo by mick bello

[infinite grain is a series of interviews inspired on microsound procedures, exploring a wide variety of topics in dialogue with artists who work with sound on installation, composition and improvisation]

Above all, she is a listener, not just attentive to sound but seduced by it, completely rapt and fascinated with the delicacy of echoes, the internal processes of time. Her work is thus a faithful evidence not only of how important is the relationship between the contemplation of sound and the process of composing with it, but also the transformation of those details of the sonic materials appearing inside and around us.

We are talking about Canada-based artist France Jobin, whose work perfectly exposes such process of contemplating the incredible amount of microsonic possibilities in the adventure of listening. Her work reflects not just a fine manipulation of sound but also a profound experience with it in the practice of being immersed on its the actual field. This makes her art to be as silent as sonic, as still as massively active, hence revealing a profound level of detail of the sonic continuum that unfolds to build and surround us.

The act of listening is crucial here, as it instinctively dictates how much sound to gather, to recycle, to process, to compose. In Jobin’s case, such way of measuring sound –both aesthetically and mathematically– is finely intertwined, as her compositions, often playing with limits of sound and its perception, create subtle dance between memory and reality, absence and presence, audible and inaudible. And despite of being open to such poetry of listening, her sounds are do not renounce to be geometrical, very precise, abstract, mathematically shaped, as beautiful sonic numbers between the acoustic and digital domains.

An appreciation of sonic subtlety is so implicit on Jobin’s approach to composition, that it would be unfair to just assume her work is about listening to sounds, mainly because her way of opening the listening experience suggests an attention to a particular level of sonic abstraction in which time scales appear as result of grains, frequencies and other elements extracted from field recordings. Molecular, atomic and granular structures of sound, both in time and frequency, appear as microsonic forms which can be shaped, combined and structured over time, generating an ecosystem of minimal elements which create a life on each listening, always with the right sounds, in the right place.

Listening becomes micro as well: molecular, quantum, granular. As sounds are made of very fine lines of frequencies, and subtle sparks of time, in the same way listening is able to be opened to the micro realm; fibers and grains of sound, as delicate as time as such, softly intertwined on each of Jobin’s pieces. Her role turns to be similar to that of a collector of sighs, a traveller of echoes, follower of the resonances and their reflections, getting merged together with no other purpose that one of attracting to the process of listening as a way of stillness, detention and suspension; listening as a stop, a way of addressing sound and letting it be. That is, to value the process of composing as a way of conjuring immersion, sonic absorption, where to contemplate what is sounding, is at the same time, to be the sound as such: be lost on listening, pointing to oneself on it, feel one with it.

Each listening experience Jobin weaves is presented as a habitat for quietism, a quiet village of sounds which despite of their artificial reproduction –as it is created with means of contemporary technology–, doesn’t lose but expand their spirit; openness that comes from the special direction of this artist to what’s so fine, perfect and exact, at the same time so organic, natural and simple, the latter not understood as ‘non-complex’, but as ‘what has been stripped of the unnecessary’ and is even expressed in a quasi-geometric and accurate form, perhaps a finer, more pure sound, a microsonic substrate of the quintessence, of subtle signals that constitute the universe as such.

Jobin’s work is therefore a sonic cosmogony, both myth and science, art and math; present in the beauty that is expressed in odes to the laws that hold matter, but also in the ineffable, what can’t be found in any science but only in full contemplation. This form of articulating scientific knowledge and contemplation, both conceptually and in the aesthetic practice, is unique in Jobin, resulting in an fascinating adventure whose rudder is the minimal sound, but whose point of arrival is infinite one, so uncertain and eternal as the art of listening it carries and suggests.

Hi France, what are you listening right now?

Hi Miguel, I listen to a lot of music when I am not working at my own projects. It varies from Miles Davis to Ryoji Ikeda, but as of late, I am somewhat intrigued by beat oriented music, whether it be techno and its various forms, and other genres. I have been listening to James Holden, Rrose, Jeff Mills, Erycah Badu, TM404 and Atom TM’s HD.

Presently, my focus is on two albums: A Day in New York, Morelenbaum 2/ Sakamoto and Divertissement – William Basinski & Richard Chartier.

Otherwise, my regular playlist includes Richard Chartier, Pinkcourtesyphone, Steinbrüchel, Elektro Music Department, Akira Rabelais, Fourcolor, Evala, Mika Vainio, William Basinski, John Coltrane, fourm, Robert Curgenven, Schneider TM, Stephan Mathieu and many more.

I wonder how was your introduction to sound and how has that changed over the years until today. What place sound has in your life?

Being a difficult child, it didn’t take long for my parents to realize they could keep me quiet and out of trouble by placing me between 2 speakers. For a child who asked too many questions and who would get overly excited over simple things like music, it seemed natural to send me off to learn classical piano.

I had trouble reconciling the fact that the sounds and melodies I fell in love with were not always defined as music: for example, the sound of tires rolling over snow.

Synchronized swimming had a decisive influence on me as well; it transformed the way I listened to traditional music. The sound system used for this purpose was often positioned on a table next to the swimming pool (late 60’s). While submerged under water, I could hear the music playing above me, and, as you might expect, it was very different. I was left to execute elaborate moves, counting time to music I could hear, but not the way it should sound. I liked this much more

Sound has always been omnipresent in my life. Being affected in a good way by synesthesia, where architectural spaces are concerned, is the driving force that compels me to create these sound explorations. Field recording provides me with rich sound sources, whose melodic qualities are often hidden; I like to uncover them.

I think there is some implicit (let’s say) precision in your work, both aesthetically as technically speaking. You seem to be so sensible to the wide variety of timbres around us, but your compositions are not so overcharged of sounds and timbres, but rather minimalist and reductionist, always featuring just the precise and enough elements. How this approach emerged and how has it evolved in your work? I also wonder how you find these ways of leading your work to be so pristine and clean, and also if it’s hard to deal with such subtlety. Why do you prefer to work with those elements at the first place?

Thank you Miguel, I am touched by your comments concerning my work. This approach manifested itself through a series of experiences and thoughts.

Playing blues and touring was a great “school of sound” for me. While touring, one is often subjected to less than perfect conditions in regards to the venue, the sound system, etc. Among the things I witnessed for instance, was that the good blues players would always talk about the “feel”. No matter how technical a musician, if he did not have that “feel”, the subtleties of the idiom were not assimilated in the playing. Less notes, more “feel” was always the aim. I realized this was my initial exposure to a minimalist approach.

Another expression often used was “being in the pocket” or “staying in the pocket”, which was aimed at the rhythm section – drums and bass – and the important relationship between the two. If they were in sync, anything was possible; if they were not, the whole structure fell apart.

These concepts shaped my listening experience. I listened to each instrument individually and to all of them, as one. We constantly had to adjust to each room we played as venues differed in construction materials, size, etc.

The decision to move towards quieter dynamics and constructions happened gradually as I began questioning myself musically, and I no longer felt challenged. One moment in particular stands out: while listening to Miles Davis Kind of Blue, it occurred to me that I may have been looking at this all wrong. I thought of a staff and notes and wondered, “What if it’s not the notes that create music, but the spaces between the notes, the rests and silences?” I applied this concept to my approach in programming sounds, that subsequently led me to minimal sound art, which, in turn, led to a new-found interest in science, quantum physics, the elegant universe, and the tiny world of particle science.

I discovered that presenting quieter works engages the listener in a different manner. Quieter dynamics does confront one to one’s act of listening; perhaps there is a need for us to re-educate ourselves. Now, we often listen while busy doing many different things. I am hoping to make people stop and listen, simply listen.

I work this way basically because it is challenging. I have to work very hard to “zone in” on every sound I create, to peel away its layers in order to get to its true essence – this process is what makes it so fascinating. I am not interested in working within my comfort zone, that’s boring. What I fear most is stagnation, so I try and stay away from anything that will create a routine.

Perhaps I should make a distinction here between routine and discipline. I am very disciplined where my work is concerned, but the approach cannot be routine. I try and work differently every time, using different methods, concepts, etc., but I work every day. I have what I like to call an “inspector 12” within me that checks everything for validity of thought, process, and clarity of intent. If it does not meet these criteria, it gets discarded very quickly.

In that way, you mention in an interview at attn something about you work with quiet sounds when composing and how important are those for triggering certain states in the listener. Why and how do you think it affects not only your workflow but the actual way of valuing the tool/technique itself? What’s the importance of technology in your artistic procedures?

Working with quiet sounds is a way of focusing in; it forces me to work from within, not from outside in. If I can draw a parallel, some actors study the personality traits of a character and can be in character without the makeup, costume, etc: this is working from within, the actor who requires make up, costume, set, etc., works from outside-in. This process enables me to be completely attuned to what I am doing. Technology is important insofar as how can I best express what I hear in my head. In that sense, I do not choose technology for what it can achieve, I choose the best technology that will enable me to express myself. Most times, I am pushing it in terms of what the technology can do for me and I go about this without reading manuals; I experiment. Technology is a tool, it does not replace substance and content, it helps me communicate in the closest possible way I intend it to be, but it is a tool, nothing more.

I wonder how much are you concerned with the limits of perception and if that is reflected in any way in your methods and approach when developing listening experiences.

Yes I am, it is important to understand everyone’s base of reference and how it can be approached to bridge the gap with sound art and electronic music. If you are playing 4/4, you are appealing to a more physical aspect of perception, one that will give you a downbeat and make you want to dance. If playing more experimental works, one appeals to a more cerebral perception that, while it may also be very physical, the reception won’t be so easy from a listener’s point of view (hearing). The same can be said of classical music or jazz.

In a live setting, the work I present must take into consideration the architectural space. Sound and frequencies react differently according to space and speaker placement. I now look at each room I play in as an instrument; it becomes part of the performance.

In a recording environment, I work differently to achieve this since I cannot guess how this work will be experienced, through a laptop with headphone, a sound system or a phone. I need to draw the attention of the listener in, to get the listener to stop and listen.

In an interview for tokafi you talk about your interest on quantum physics and how that conception of the universe deeply affects you, which is even directly present in works as Valence (LINE), Illusion of the Infinitesimal (Baskaru), among others. What it means for you to discover a way of conceiving the cosmos so different from what we commonly experience? Also, how do you relate those scientific theories with microsound, which is also atomic, quantum, etc? How the actual link between art and science that happens around microsonic conceptions actually influence your way of working?

Quantum physics describes the nature of the universe as being much different than what we see. This is exciting to me because every field recording I make, I listen to in this way, I do not hear it as it sounds, rather, I hear what I can take from it to create a new sound.

Looking at the world through this lens has really helped me in my own understating of myself. I recently read A brief history of time by Steven Hawking, and although it is an older book and he now disagrees with certain ideas he discussed in it, it is a fantastic book if one has no prior physics background. It goes about explaining the history of many theories and how each scientist went on to disprove or improve on a given one. For instance, I had no idea there were 2 theories of relativity.

General relativity: abandons the idea of absolute time and special relativity, is all about what’s relative and what’s absolute about time, space, and motion, meaning that the laws of science should be the same for all freely moving observers, no matter what their speed.

What I like about all this is that it teaches me that life is in constant flux; the world in is constant flux. It helps reconcile me with the idea that we are just passing through.

1: “For instance, a scientific theory is just a mathematical model we make to describe our observations, it exists only in our minds, it is meaningless to ask: which is real, ‘real’ or ‘imaginary’ time? It is simply a matter of which is the more useful description.” – A Brief history of time, Stephen Hawking, p. 179, Bantam Book (Trade paper edition), 1990

2: “Singularity: because mathematics cannot really handle infinite numbers, this mean that the general theory of relativity (on which Friedman’s solutions are based) predicts that there is a point in the universe where the theory itself breaks down. Such a point is an example of what mathematicians call a singularity.” – A Brief history of time, Stephen Hawking, p. 46, Bantam Book (Trade paper edition), 1990

This pursuit of knowledge in science translated to a similar path in my music and naturally influenced my approach to sound and composition. My sound processing slowly became about the peeling away of each superfluous layer until I reached the essence of each sound. From that, it effortlessly moved to each movement within a piece and the composition as a whole. My superficial understanding of science helps reconcile certain concepts I have and, in my work, the only link between science and music is my interpretation of certain scientific principles translated into sounds and composition.

How is balance and approach toward electronic vs. field recorded/acoustic sound present in your work? How important is for you to merge them, preserve some of their qualities or alter what they produce for perception?

My creative process consists of gathering field recordings and processing them to an unrecognizable state. Many sounds are available to us, but we are conditioned to tune them out. I transform, manipulate/recycle sounds of our everyday life, to be re-presented in a new light.

I recycle sounds.

Relating to that, there is sonic matter. Do you value sound as some kind ‘material’? Something beyond, perhaps? I wonder how your own definition of sound gets placed among the transitory yet present nature of its physical manifestation.

Sound is intrinsic to life, in the womb one cannot see but can hear; this is temporary. It introduces us to this nice little paradox, just like sound and time – we are simply passing through, always transient.

Following that, I wonder if you could expand a bit more about how this relates to your practices of listening, during your daily life, during field recording, composing, performing, etc. I mean how your relationship with sound affects the whole spectrum of sonic experiences and connections and also how different situations alter your way of listening.

At times, it’s a blessing or it can be a curse, I am attuned to listening more than anything else in life. As much as I can recount musical passages, overused gear and plugins, I also hear everything else more acutely, which, at times, can be very unpleasant.

I discover cities through exploring their sounds. I have found that, while travelling, all senses are heightened and sharpened as one tries to familiarize oneself to new environments. This puts me at great advantage to find and record new raw material. While composing, there is a more intimate relationship; I am very attached to my sounds while composing, I feel I need to treat them gently and honor them. Once I am done, I completely let go.

It is something innate in me that has me relating to sound the way I do, the architectural synesthesia, the understanding of sound in a space and how it relates to the architecture, as well as how the architecture shapes it.

I would say this is the strongest influence, which explains why I like to work in situ in an installation context.

My state of mind dictates how I listen.

Do you have a particular criterion for choosing your palette of sounds. How you generate, pick, organise or define where to place them?

I generally work within a geographical region as most of my field recordings are done while on tour, travelling. They are somewhat a sound diary, which reminds me where I was and the wonderful people I was so fortunate to have spent time with. Each recorded moment draws on different of forms of programming, colors and nuances that emerge from the experiences as well as my memories of it all.

Next, I will program the sounds by listening to these recordings, literally splicing small segments to work with. In 20 minutes of recording, I can create 200 different sounds with this splicing method, programming with various plugins, changing color, frequency, timbre etc.

The placement of sounds is very instinctive, the nature and quality of the sounds is so important to me that when it comes to composing, it is almost like a puzzle: some sounds fit, others don’t, some sounds like each other, others don’t.

You also talk about the intentions you have with your work, by using certain dynamic range, quiet sounds and an immersive space/situation, so you can make people stop and listen. How this interest on quieting people and inviting them to listen emerged? What to you think about the link between listening and detention and how important is for you to dispose ourselves to the contemplative experience of sounds? Would you see that process as something spiritual, therapeutic or socially important in a way?

I think we live in a society that demands a quick fix for everything. People are generally stressed, running from one thing to the next, without ever having one moment to stop and reflect. My work, I hope, acts as a catalyst and incites people to stop and pause. In doing so, if I manage this much, my work really becomes secondary as it has achieved its aim – to get people to listen, and, perhaps, to quiet down enough to listen to themselves. In that respect, only the listeners will determine the nature of their own experience, and, at that moment, my work becomes secondary.

Having your experience with immerson, I wonder how is your conception of the sonic space and the actual exploration of the listener point/comfort. How do you think it affects not only the sounds but the listening experience as such? Could you tell us about any experience you remember from the states or situations triggered at those gatherings?

immerson came about from my experiences both as an artist and a member of the audience. I noticed how very little care was given to the actual physical comfort of the audience, which I believe affects their ability to listen. The premise for immerson was simple: I thought that one cannot expect an audience to be physically uncomfortable while confronted with intellectual discomfort. I felt that if people were physically comfortable, they would be more receptive.

With immerson, this is what happened. Some people would be so comfortable that they would slip into this half-awake half-asleep state, where music just hovered over and around them.

I have also concluded that the context of presentation of works is fundamental to the intention communicated, which must be respected, be it minimal, lo-fi, noise, etc. Each one requires a specific approach in the context of presentation to ensure that an artist’s work being presented in the best possible way. When that happens, it is an honest proposition, and the public will react according their frame of reference, but, at least, the intent is clear.

Photo by Antonello Carbone taken during Liminaria Residency, Italy

And how this spatial concern affects your work in the studio? What’s the difference with the performance environment in terms of your approach, intention and way of working?

If I may start with a small parallel, an architect creates works that occupies a space. I would say I create sculptures that fit in the flow of time and perception. The environment architecturally shapes the pieces and how they will be heard. In installation and concert works, for instance, I may position speakers in specific ways to respond to the architecture, therefore creating a sound sculpture without it being an object. It is about presenting a work that is much different that which one hears dependent on one’s placement.

In my studio, my approach is entirely different. Here, I can really focus on clarity and precision. In a concert or an installation, I am thinking outward; the outcome is decided by external factors. In my studio, where I program sounds and compose, it is a much more intimate relationship to sound – a direct connection that I can exploit as I wish, not dictated by outside factors. I can obsess over a fade, a transition or a 2-second segment if I want.

The space you create in your compositions is often so clean and sublime that silence and sound become one; sometimes your silence is so sonic and your sound is so silent and I find that truly fascinating as I feel deeply in my own experience, often giving me an impressive sense of embodiment and completion that leads me to think your ‘use’ of silence as a sonic element, reflected in the fine sounds you choose but also in what it causes in terms of mental states. Following that, what is your concept of silence? Do you think about ‘it’? Also, do you think in some way you compose ‘with’ it?

I do think about it greatly; it is something I finally understood from my prior musical training. As I realized that the rests and pauses were the architect of the notes surrounding them, I also understood silence as an intrinsic part of my sound. This is how I approach programming: reaching for the unique essence of each sound enables me to leave space for silence. When I am using one of my favorite hi pitches, silence is below that frequency; the frequency exists to let you hear what is not there, even though it would appear it is all you hear. The amplitude also affects this in a nice way; if I am working with low volume, silence will seem to be more present while changing the nature of the sound, while working with loud volume enhances certain frequencies.

Why your interest towards simplicity? I guess your minimalist approach to sound comes from an actual minimalism that is implied in your daily life. How is that relationship? Are you influenced by minimalism in other ways rather than sound? And how do you think those ways actually relate to sound?

Simplicity is really a state of mind I am attempting to reach. My life is really chaotic with family, travel, and so on that, often, my work, in some way, represents a headspace I am trying to grasp. This minimalist approach is more a mental one than it is present in the physical realm of my life, although I do appreciate minimal art, architecture, and design – they all help me reach the calmness I am aiming for. For instance, in my studio, I have only one print on the wall facing me, Mono.Poly.Chr Print by Richard Chartier, based on his designs for the two double cd releases on LINE by Bernhard Günter. This print is a solid grounding force if I feel I’m too scattered.

How was your recent experience on Empac? I wonder how did you manage the relationship between your sound work and the features of that piece such as the speaker system, acoustics and light. Also, how is typically your approach to these multichannel explorations of your work? Is that related to your “immersound” philosophy?

Empac was truly incredible! I am still reeling from the experience. This project, curated by Argeo Ascani, was a residency that resulted in a concert. I arrived at Empac with an idea that I wanted to explore, knowing that I would have to develop it further on site.

On my first visit of the concert hall, I was able to not only realize the full scope of the project, but, most importantly, the multitude of possibilities that I was faced with. The biggest problem was to make the right decisions for each speaker placement, each sound to use and where to use it, etc. This is as scary as delightful a position to be in, exactly where I like to be in my full creative zone. For that purpose, I spent 10 days in the concert hall, playing, testing, and walking around a lot in the hall to test every sound in specific speakers (30 to be exact) as well as the plenum (floor vents).

My approach to live concerts is very different from immerson, though the idea of exploring the limits of perception remains. immerson is an event I created for other artists to perform in, dedicated to minimal music, which takes place in a very intimate context. When I perform live, in a big venue such as the concert hall of Empac with a good system, anything goes in terms of pushing those limits. For this reason, my live shows are very physical contrary to my recorded works, which deal with a different listening context and approach.

The concert hall at Empac combines the outstanding acoustics, refined materials, and the comfort of great concert halls of the past, yet with the additional flexibility and technology of the 21stcentury. The hall’s superior acoustics comes from a number of innovations. Convex walls and other shaped surfaces allow performers or loudspeakers to be anywhere in the hall, redefining the notion that music comes only from the stage. A fabric ceiling was developed for the first time ever for both its acoustic and aesthetic properties. Air rises quietly from under the seats rather than being forced down by noisy fans, this is the plenum.

At EMPAC, I was able to delve in areas I do not normally explore, including beats, which I had not yet performed publicly. These beats were issued and recorded from a previous artist’s residency at EMS in Stockholm in April 2015, using the Serge and Buchla 200 modular synthesizers. I presented a new work structured for the EMPAC Concert Hall and I also collaborated with Alena Samoray, who created a subtle lighting design that was complementary to the sounds. Alena uses the architecture for lighting the same way I use it with sound.

Alena and I now have a new collaborative sound and light multichannel piece:

4.35 – R0 – 413 to be performed in concert or presented in an installation context.

Last but not least, could you please recommend us something to read or listen? What moves your interests lately?

Reading: Well, first of all, would be A brief history of time by Stephen Hawking and I am now reading Hyperspace by Michio Kaku.

Listening:

Miles Davis, Kind of blue

Donaccha Costello, together is the new alone

Akira Rabelais, The Little Glass

Steinbruchel, narrow

:zoviet*france:, the decriminalization of country music

William Baskinski, variations for piano and tape

Evala, Acoustic Bend