France Jobin

Sans repères

Japan, popmusik records

popmusikrec_002

LP (180g Heavy Vinyl)

Edition of 300

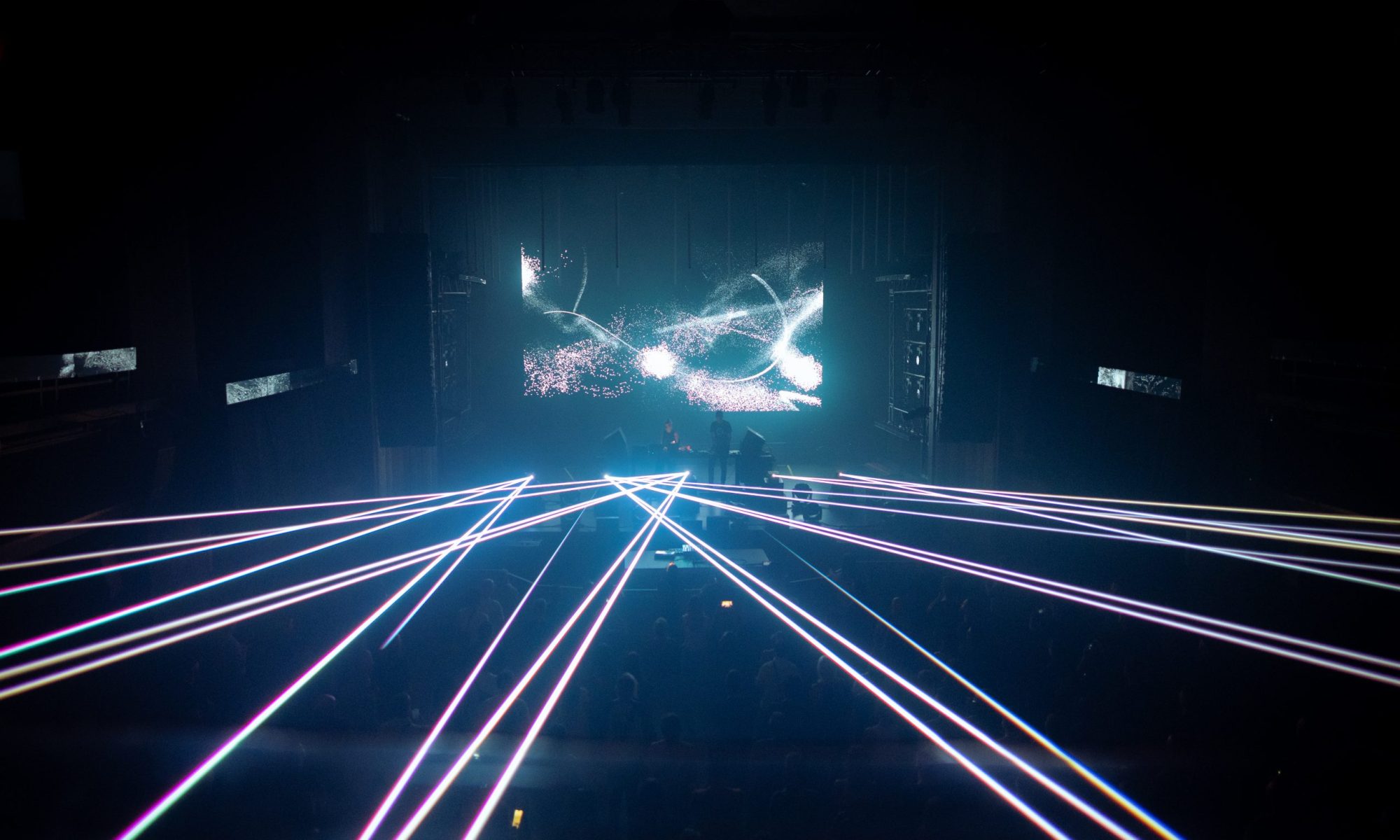

Sans repères. Sin prácticamente ninguna referencia a la que poder atarse, sin punto alguno al que poderse afirmar más que la forma en unos sonidos ignorados se presentan. Atravesar a través de los canales por los cuales circula la información virtual puede ser una actividad muy tediosa como también estimulante. Siempre me ha parecido interesante la forma como esa información se expone, a veces incluso más que el contenido mismo. La estética de la materia, la forma sobre el fondo. Resulta fascinante ver el orden de las cosas, líneas de separación y textos en tamaño reducido que exteriorizan datos comprimidos. A veces uno puede perderse dentro de ese espacio de ceros y unos, sentirse absorto en la belleza del diseño en HTML. En uno de esos instantes pude descubrir un pequeño sello que solo contenía escasa información acerca de los sonidos que él se albergaban y, más importante, las imágenes de cómo esas notas se expresaban en forma real, una aproximación en representación hexadecimal de un hermoso ruido. Y volvemos a la realidad. Popmuzik es una plataforma con sede en Fukuoka, Japón, que operó también como tienda de discos y además como productora de eventos organizando varias presentaciones de interesantes artistas. Sin embargo, es ahora recién que se aplica a la publicación de ediciones propias. Así es como aparecen sus primeras dos impresiones en formato vinilo y en tiradas limitadas. Dos trabajos donde la belleza exterior se encuentra en concordancia con la belleza que se extrae de los oscuros surcos.

France Jobin es una artista canadiense que antes solía publicar sus trabajos bajo el nombre de I8U, una historia desarrollada por más de diez años. La compositora de Montreal decide hace no mucho tiempo atrás descubrir su nombre y dejar de estar escondida bajo esa otra identidad. De esa manera es como aparece “Valence” (LINE, 2011) [184] y, recientemente, “The Illusion Of Infinitesimal” (Baskaru, 2014) [326],“donde la artista se encierra todavía más en las panorámicas silenciosas… Tres piezas, tres prolongados desarrollos de minimalismo electrónico y ruido ambiental reducido a su expresión más esencial… El universo sonoro de Jobin se concentra en sí mismo, una instrospección que limita lo más posible cualquier estridencia, dejando que las explosiones de sonido se conviertan en implosiones… ‘The Illusion Of Infinitesimal’, estas composiciones de France Jobin conforman una enorme obra de ruido digital estático, la ilusión de la quietud en manchas minúsculas y notas que se desvanecen en el silencio”. En este su tercer trabajo de esta nueva etapa de su trayecto artístico Jobin despliega y ordena sonidos recolectados de forma natural, un trabajo que amplía aún más los límites de su obra, dejando el silencio por la quietud y el estruendo contenido de armonías de formas imprecisas. Sans repères / sin referencia. Un trabajo que tiene la forma de 12 pulgadas, la belleza a 33 y un tercio de revoluciones por minuto, una obra presentada impecablemente con una fotografía de Eri Makita en la portada y con un elegante diseño a cargo de Keiji Tanaka en cartón color naranja en su interior. “Sans repères”, popmuzik02, la segunda referencia de este nuevo label de música panorámica es una obra hecha desde registros externos los que son procesados para dar existencia a dos prolongados desarrollos de una música fascinante. “Grabaciones de campo en Fukuoka y Yanagawa durante un paseo en bote en sus canales. Creado enteramente con grabaciones de campo reunidas mientras estaba de gira en Japón, ‘Sans repères’ explora las posibilidades llevadas a cabo en la ausencia de absolutos puntos de referencia”. Lo que fue recogido junto al agua quieta al pasar por el proceso aplicado por la artista canadiense resulta en pausados desarrollos de energía estática, electrónica brillante que recompone el sonido natural y lo transforma en armonías digitales. La raíz original de esta música espontánea queda escondida detrás del sistema de pulsos y unidades binarias, líneas ocultas de ruido que se transforman en tratamientos lumínicos de notas y espacios amplios. Lo cierto es que de las formas primeras solo quedan rastros borrosos. El procedimiento aplicado sobre la materia prima que sirve de base a estas composiciones se reduce a una idea e impresiones abstractas, separando sus átomos en fragmentos que luego son esparcidos sobre un lienzo blanco de partículas de luz y acordes decimales extendidos. Dos notas, apenas seis segundos que desaparecen en el vacío. Un silencio, apenas un segundo, incluso una fracción de él. Una melodía interrumpida, un loop que se propaga con su pureza imperfecta hasta que el espacio que separa una porción de otra queda reducido a cero.“Sans repères”, y la música que se va formando de manera imperceptible, las variaciones que se desarrollan de forma invisible. Un ruido intangible que adquiere tonos diferentes conforme hay más presencia de luz. Hasta que ocurre un quiebre, un instante donde sobre ese lienzo cae polvo de estrellas generando nudos repetitivos de partículas ásperas. La belleza de la imperfección que más tarde se convertirá en hilos de electrónica inmaterial y después en un estruendo abrasivo. Casi veinte minutos de una música gloriosa. “Sans repères” tiene una estructura similar. Sin embargo, los matices hacen que sea una obra nueva dentro de su uniformidad. Fragmentos entrelazados creando un bucle interminable que termina por ser cubierto por la densidad desvanecida de las armonías sintéticas que se vuelven en superficies impolutas con pequeñas manchas de ruido, los restos del polvo estelar que cubren esta otra cara, la arena del río que traspasa la naturaleza fluvial hasta la naturaleza artificial. Al final solo quedarán los remanentes, partículas digitales que envuelven el terreno vectorizado. “‘Sans repères’explores the possibilities brought forth in the absence of absolute points of reference”. Sintetizando las bondades que presentaban sus creaciones anteriores, este trabajo utiliza como punto de partida unas grabaciones de las cuales solo quedan su materia más pura, una materia física que se convierte en una substancia intangible y una música de delicadeza variable. “Sans repères”, una obra surgida desde la belleza análoga que luego de un fascinante proceso desplegado por France Jobin culmina en hermosas piezas de ruido digital y notas transparentes.